The Gray Area in Creative Industry

Respect and Pride, Brands and Stories, Mindsets and Markets

To illustrate the points I'm about to make, let me briefly tell you about the Corthay Arca

About 25-30 years ago, French artisan Pierre Corthay introduced a two-eyelet derby shoe with a smooth toe, named Arca. This shoe gained worldwide attention for its unique approach: a derby shoe that was as elegant and formal as an Oxford.

To this day, it remains the most iconic design of the brand and one of the most influential in modern shoemaking. Its impact is so profound that nearly every shoemaker around the world has created—or will create—their version of the two-eyelet derby (or high vamp derby).

Of course, Corthay himself understood that he couldn't copyright the design (after all, he wasn't the first to invent it, just the one who brought it to life). Similarly, no one can copyright the design of a shirt, jeans, or baseball cap.

Therefore, it's entirely normal for hundreds, if not thousands, of brands worldwide to take these designs, manufacture them, and sell them.

Image source: www.corthay.com

The voluntary decision not to infringe on intellectual property.

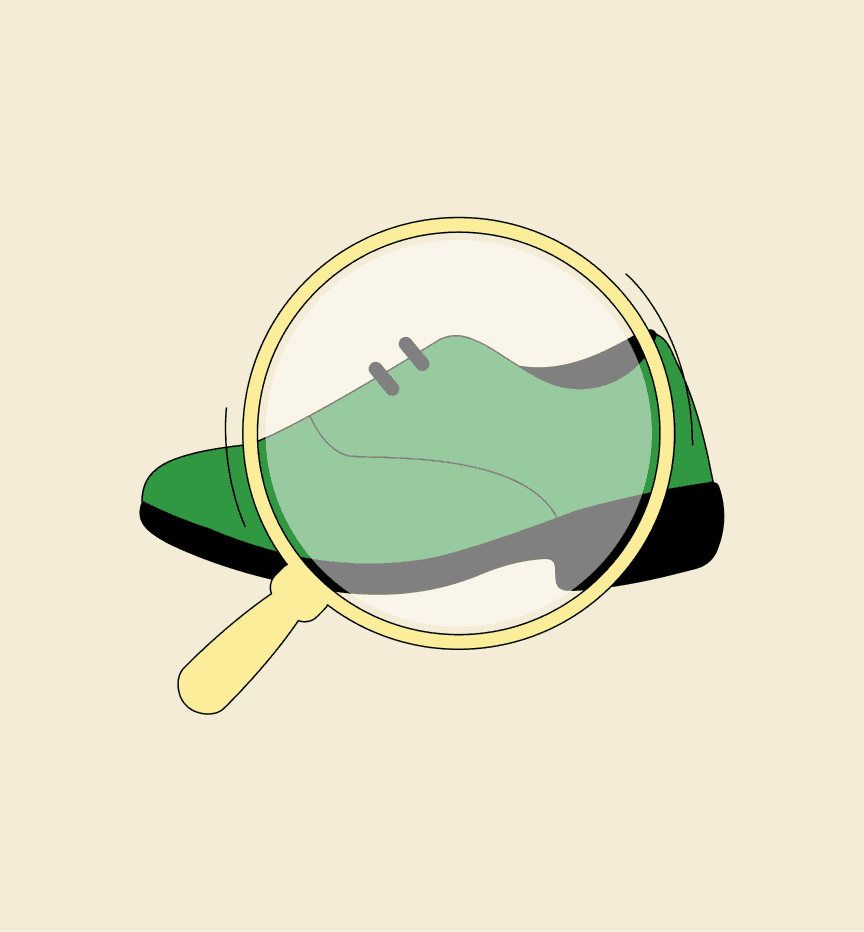

However, if you take a closer look, you might notice something "unique" about the Arca: the knot of the laces is placed at the second eyelet, not the first, as is customary with most shoes.

If you're curious enough to investigate, you'll find that Corthay shared a short story explaining why he did this. But when you think about it, this detail doesn't contribute much to the shoe's aesthetics or functionality.

So, the story is simply a way to legitimize one of the "personal touches" Corthay wanted to infuse into his shoe: "There may be thousands of two-eyelet derby shoes on the market, but there will only ever be one Arca."

When you look at the market, you'll see that almost no brand, big or small, ties their laces in this style when creating their two-eyelet derby shoes. Part of the reason is that it adds no value to their product, and part of it is out of respect for Corthay and their own brand identity.

They want their products, while inspired by Corthay, to be distinct and not mere copies of his work.

The Gray Area in Creative Industry

This leads us to a discussion about the gray area of intellectual property in creative design.

There's no law that strictly prohibits, nor any market that would boycott, a shoe brand just because they tie their laces like Corthay. But brands voluntarily choose not to.

This phenomenon can be seen in many other cases: it could be a signature cut for a suit pocket flap, or a bartender always stirring their cocktail mix exactly 12 times clockwise instead of 10 times like others.

These details don't significantly impact the final product but are simply ways to keep creativity alive, give the creator a story to tell, and carve out a unique space in the world.

As a result, people often avoid copying them.

Some of the arguments I received.

"But my brand is small and have too many things to worry about..

...like generating revenue and keeping the business alive." Maybe you don't have time for creativity, money for R&D, or the desire to hire an Art Director or run an elaborate storytelling marketing campaign. The solution for this case is incredibly simple: just do the basic things that everyone else does to sell products. You may not be able to innovate like craftsman Antonio De Torres did with the Eye of Ra Milanese buttonhole, but instead of copying his work, you can still sew the standard Milanese buttonhole that everyone uses, and you'll still have a product to sell.

"Customers mostly don't care about these minor details."

Yes, you can copy someone else's intellectual property, and most of your customers won't notice and will still buy your product. Again, this is a gray area—salespeople are storytellers and guides for customers, and sometimes, influential consumers with a voice in the community also play a role in painting this gray area to their liking. So, the question arises: Do you and your business want to contribute to creating a healthy market that respects intellectual property, a place where creative minds feel safe to tell great stories? Or do you want to see the fear of intellectual property theft happening everywhere, with no one standing up for you when it happens, leading to a gradual decline in creative passion?

"Others have been copying for centuries before developing their unique identities"

True. However, the Vietnam government's "Leapfrog" strategy is equally valid. Vietnam economy maybe 100-200 years behind other countries, but does that mean our thinking should start 100 years ago and always remain behind? Instead of "Start with indiscriminate copying and think about it later when we have money," why not "Start with the basic designs that the entire market agrees to use, and when we grow, we'll innovate"?

Conclusion

This article is lengthy and raises many questions without clear-cut answers because we're in a gray area. Therefore, there may be many correct paths, or perhaps all paths lead to the same outcome (for example, even if intellectual property awareness is raised to a very high level, if there are policies that heavily tax creative industries or implement strict prohibitions, it would still be challenging for creative industries to flourish).

So, I'd like to emphasize that I don't intend to offend anyone with a different perspective in this gray area—I just want to share the viewpoint of someone who is always in the mindset of fighting for the rights of those working in creative fields.

From the story of intellectual property in small things like tying shoelaces or sewing buttonholes, I hope everyone realizes that if we want to achieve great things, our mindset must start with building from small, easy actions—those of people who seem to have little impact on the big picture.